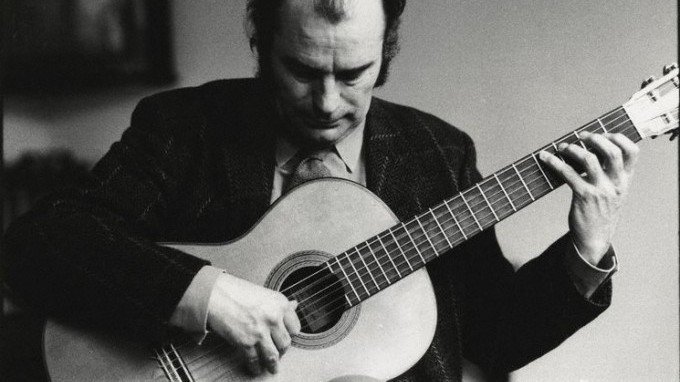

For the greater part of the 20th Century the Spanish musician Andres Segovia was the undisputed maestro of the Classical Guitar. Many professional classical guitarists of today were students of Segovia, or students of his students. Segovia died in 1987 at the age of 94. “The final two decades of Andres Segovia long life coincided with many developments in the contemporary repertoire and a sense of change generally in the structure of guitar recitals. In particular the influence of the Early Music movement, at the peak of its progress in the 1970s and 80s, made it rather unfashionable to perform music of the vihuela or baroque guitar eras, let alone music for the renaissance lute, on the modern guitar. Many players began to perform recitals on vihuelas, actual or reproduction baroque guitars, and Panormos. Lute virtuosity, whether renaissance or baroque, hitherto rare, became an available commodity, including continuo and accompanying skills.” Also there was a new repertoire developing with “compositions by Tippett, Henze, Carter, Brouwer, Reich, Takemitsu, Koshkin, Nobre, Rak, etc, brought about a new aural landscape and unprecedented perspectives for recitalists. In concerts performers jettisoned the chronological approach ranging from the Renaissance to the present day, and shaped their presentation differently, often, like pianists, preferring one or two large works in each half rather than a packed programme of shorter items racing across the spectrum of styles.”

Coincidental with the final decades of Segovia’s life Julian Bream, John Williams, and Alirio Diaz rose to prominence. Segovia was a magnificent presence in the Classical Guitar world but each of the guitarists mentioned emerged from Segovia’s influence and managed to carve out his own particular niche in that very select world of classical guitar. While Segovia enlarge the repertoire for the instrument it is undeniable that his tonal palette was decidedly Spanish.

Alirio Diaz was a Venezuelan musician and as such his repertoire contained a significant number of works by the South American composers Augustin Barrios and Antonio Laurio. His tonal palette was brighter and more aggressive than his teacher Segovia.

John Willams was a flawless technician with a vast standard classical repertoire but he also experimented with more “modern” sounds. Perhaps he was a more cosmopolitan musician than his contemporaries.

Julian Bream, on the other hand was decidedly English and, maybe to prove a point, he was a champion of the Elizabethan Lute and the music of John Dowland. “Bream’s recitals were wide-ranging, including transcriptions from the 17th century, many pieces by Bach arranged for guitar, popular Spanish pieces, and contemporary music, for much of which he was the inspiration. He stated that he was influenced by the styles of Andres Segovia and Francisco Tarega. Bream had some “sessions” with Segovia but did not actually study with him. Segovia provided a personal endorsement and scholarship request to assist Bream in taking further formal music studies. Segovia predominantly associated his guitar skills to music compatible with the guitar’s Spanish and Latin roots. Julian Bream’s style expanded the use of guitar into more contemporary genres. Bream’s work showed that the guitar could be capably utilized in English, French, and German music. Bream’s playing can be characterized as virtuosic and highly expressive, with an eye for details, and with strong use of contrasting timbres. He did not consistently hold his right-hand fingers at right angles to the strings, but used a less rigid hand position for tonal variety.” … Wikipedia

Bream met Igor Stravinsky in Toronto, Canada, in 1965. He tried unsuccessfully to persuade the composer to write a composition for the lute and played a pavane by Dowland for him. The meeting between Bream and Stravinsky, including Bream’s impromptu playing, was filmed by the National Film Board of Canada in making a documentary about the composer…… Wikipedia

He lived for over forty years at Semly, Wiltshire, at first dividing his time between there and Chiswick, London, then moving permanently in 1966 to a Georgian farmhouse in Semley, living there until 2008.[37] In 2009 he moved to a smaller house at Donhead St Andrew, Wiltshire. Bream was keen on the game of cricket[ and was a member of the Marylebone Cricket Club. ….. Wikipedia

Julian’s recording career included at least 30-50 LPs and CDs and four Grammy Awards.

Julian Bream (1933-2020) died on 14 August 2020, at his home at Donhead St Andrew. He was 87years old.

@@@@@@@@@@@@

Some video clips of Julian Bream

@@@@@@@@@@@@

Julian Bream Documentary

@@@@@@@@@@@@

In the years since then Jazz has continued to evolve into a plethora of styles and a number of musicians who came to fame in Blue Note years have continued to perform well into their sunset years with major contributions to the art form. This obituary in the New York Times, April 16, 2020 by

In the years since then Jazz has continued to evolve into a plethora of styles and a number of musicians who came to fame in Blue Note years have continued to perform well into their sunset years with major contributions to the art form. This obituary in the New York Times, April 16, 2020 by

September 21, 1934 – November 7, 2016

September 21, 1934 – November 7, 2016 Bobby Hutchinson and Gary Burton careers’ both somewhat overlapped Jackson’s and they both rose to fame in the 60’s and 70’s. They were the new generation who favored the use of four mallets (two in each hand) that allowed for a more complex pianistic style of performance. Although somewhat now retired Gary Burton is still around and is probably still performing in a semi-professional capacity. Bobby Hutchinson passed away on August 15, 2016 surrounded by his family in the living room of his long time home in Montara, California. He was 75 years old.

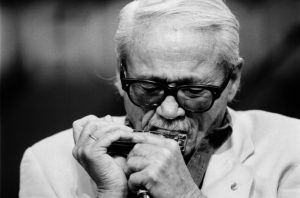

Bobby Hutchinson and Gary Burton careers’ both somewhat overlapped Jackson’s and they both rose to fame in the 60’s and 70’s. They were the new generation who favored the use of four mallets (two in each hand) that allowed for a more complex pianistic style of performance. Although somewhat now retired Gary Burton is still around and is probably still performing in a semi-professional capacity. Bobby Hutchinson passed away on August 15, 2016 surrounded by his family in the living room of his long time home in Montara, California. He was 75 years old. known as “Toots”. The Chromatic Harmonica does not have the same historical traditions of other jazz instruments so he is literally the first of his kind. Although he has played with all the great jazz soloists, including Charlie Parker, he is best known for his composition Bluesette. He died in Brussels on August 22, 2016. He was 94 years old.

known as “Toots”. The Chromatic Harmonica does not have the same historical traditions of other jazz instruments so he is literally the first of his kind. Although he has played with all the great jazz soloists, including Charlie Parker, he is best known for his composition Bluesette. He died in Brussels on August 22, 2016. He was 94 years old.