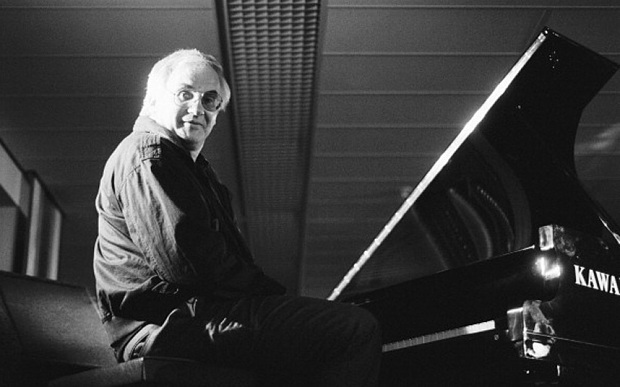

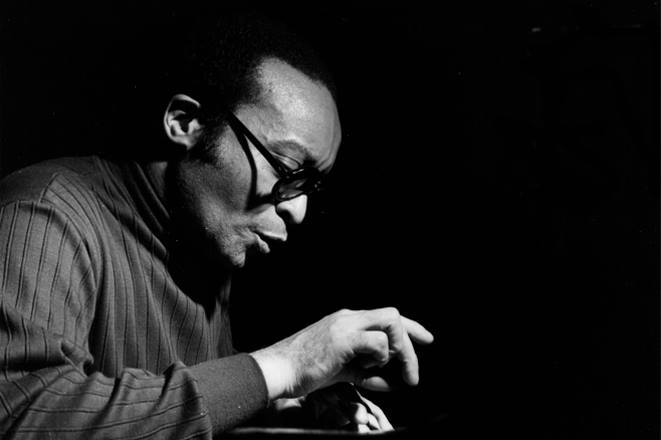

At a concert during the the last European tour of the Miles Davis / John Coltrane Quintet in 1960 a lady in one audience stood up during a John Coltrane solo and pleaded “please make him stop”. I am sure that would be the reaction of most audiences to the music of Cecil Taylor. Even in Jazz circles Cecil Percival Taylor (March 25, 1929 – April 5, 2018) is not exactly a household name. He was a classically trained American pianist and poet and is generally acknowledged as one of the pioneers of the Free Jazz movement. His music is characterized by an extremely energetic, physical approach, resulting in complex improvised sounds that frequently involve tone clusters and polyrhythms. His piano technique has been likened to percussion – referring to the number of keys on a standard piano as “eighty eight tuned drums”. He has also been described as like “Art Tatum with contemporary classical leaning”. The Canadian classical pianist Glenn Gould has been reported as saying “Cecil Taylor is the future of piano music”. It is an interesting comment from a musician who is famous for his precise interpretations of the music of Bach. Taylor is from the opposite end of the musical spectrum. Gould’s interpretations are architectual musical masterpieces while Taylor’s musical musings are more like splashes of molten lava.

Taylor is outside the orderly progression of jazz piano styles of the past century. The normal historical flow of American piano music goes back to the almost classical formalism of Louis Moreau Gottschalk, Scott Joplin, Jelly Roll Morton, and then onto the improvisational styles of James P. Johnson, Earl Hines, “Fats” Waller, Teddy Wilson, Art Tatum, Nat ‘King” Cole and then the moderns – Bud Powell, Oscar Peterson, Bill Evans, Herbie Hancock, Keith Jarrett etc. Taylor stands way outside that tradition. The only pianist that might claim some connection is the Thelonious Monk and he is better known and appreciated as a composer. Like Monk Taylor’s public appearances were performances in the true meaning of the word – music, poetry, dance. At the center of his art was the dazzling physicality and the percussiveness of his playing — his deep, serene, Ellingtonian chords and hummingbird attacks above middle C — which held true well into his 80s. Classically trained, he valued European music for what he called its qualities of “construction” — form, timbre, tone color — and incorporated them into his own aesthetic. “I am not afraid of European influences,” he told the critic Nat Hentoff. “The point is to use them, as Ellington did, as part of my life as an American Negro.” In a long assessment of Mr. Taylor’s work — one of the first — from “Four Lives in the Bebop Business,” a collection of essays on jazz musicians published in 1966, the poet and critic A. B. Spellman wrote: “There is only one musician who has, by general agreement even among those who have disliked his music, been able to incorporate all that he wants to take from classical and modern Western composition into his own distinctly individual kind of blues without in the least compromising those blues, and that is Cecil Taylor, a kind of Bartok in reverse.” Because his fully formed work was not folkish or pop-oriented, did not swing consistently (often it did not swing at all) and never entered the consensual jazz repertoire, Mr. Taylor could be understood to occupy an isolated place. Even after he was rewarded and lionized his music has not been easy to quantify. If improvisation means using intuition and risk in the present moment, there have been few musicians who took that challenge more seriously than Mr. Taylor. If one of his phrases seemed of paramount importance, another such phrase generally arrived right behind it. The range of expression in his keyboard touch encompassed caresses, rumbles and crashes. – (excepts from Wikipedia).

Taylor may not have had a big following but he was not without honors during his lifetime. Even after he was rewarded and lionized — he was given a Guggenheim fellowship in 1973, a National Endowment for the Arts Jazz Masters award in 1990, a MacArthur fellowship in 1991 and the Kyoto Prize in 2014 — his music was not easy to quantify nor did it have a great following. There was no academy for what Cecil Taylor did, and partly for that reason he became one himself, teaching for stretches in the 1970s at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, and at Antioch College in Ohio. (He was given an honorary doctorate by the New England Conservatory in 1977.) Not until the mid-1970s, Mr. Lyons told the writer John Litweiler, did The Cecil Taylor Unit have enough work so that member musicians could make a living from it — mostly in Europe. Although classically trained his comment on written music bears repeating – “When you think about musicians who are reading music,” he said in “All the Notes,” a 1993 documentary directed by Chris Felver, “my contention has always been: The energy that you’re using deciphering what the symbol is, is taking away from the maximum creative energy that you might have had if you understood that it’s but a symbol.” (excepts from Wikipedia). I agree with the comment but most of us mere mortals have to start somewhere and once the music is under your belt then perhaps the written symbols should be discarded.

In some ways he reminds me of Frank Zappa. Frank was a “rock” musician who was very distinctly outside the traditions of Rock and Roll. Just try and jam along with a Frank Zappa recording and I think you will get my meaning.

@@@@@@@@@@@@

a night of pulsing rhythms, beautiful melodies and great lyrics delivered with artful arrangements and solo improvisations by a group of stellar musicians from the Nelson area. The drummer Steven Parish and bass player Mark Spielman anchored the band for

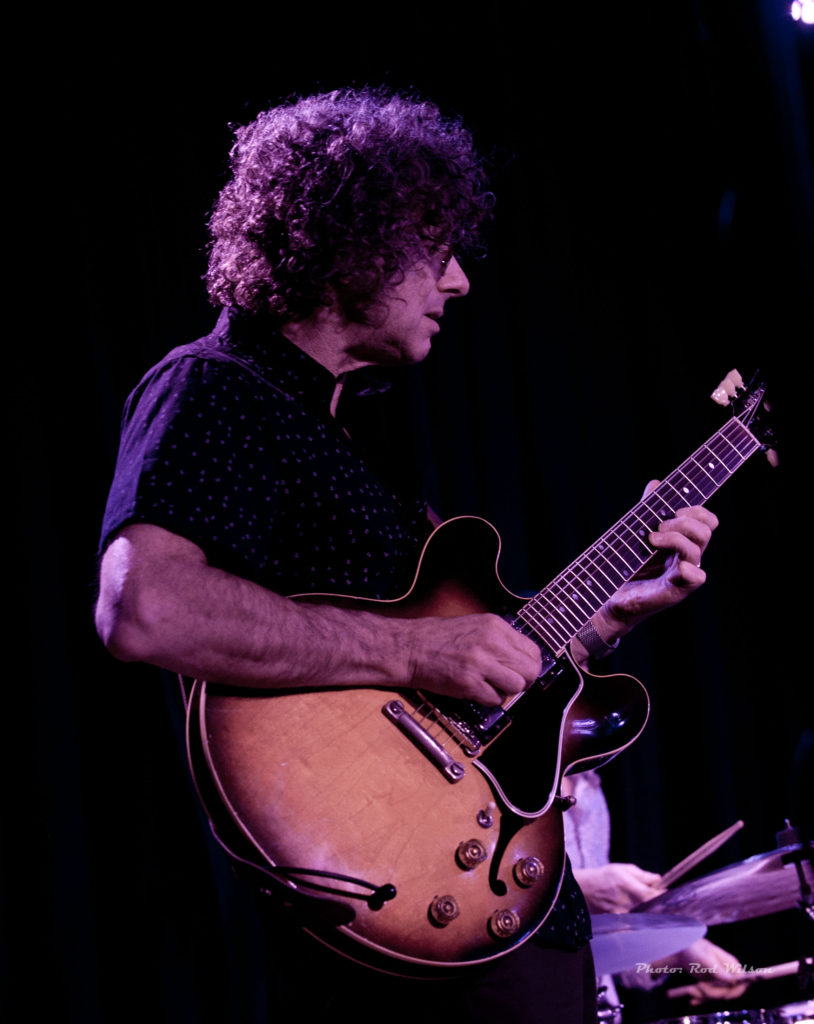

a night of pulsing rhythms, beautiful melodies and great lyrics delivered with artful arrangements and solo improvisations by a group of stellar musicians from the Nelson area. The drummer Steven Parish and bass player Mark Spielman anchored the band for  the rhythmic, melodic and harmonic adventures of Melody Diachun on vocals and shakers, Clinton Swanson on tenor sax and flute and Doug Stephenson on nylon and steel string guitars. Most of the Bossa Nova material was from the pen of Antonio Carlos Jobim and included Quiet Nights (Corcovada), If You Never Come to Me, The Girl from Ipanema, Samba do Aviao, One Note Samba, Dindi, and a nice mish/mash of Insensitive with the Beatles tune Yesterdays. Most of the songs were sung in English with the occasional foray into Portuguese. Although not exactly a Bossa Nova song, but never-the-less appropriate for the evening, the group performed Horace Silver’s jazz classic Song for my Father. Horace’s father came from the Cape Verde Islands that, coincidently, has a rich Portuguese based musical heritage similar to Brazil. Interspersed among Jobim’s songs there were the following Beatles songs Hard Days Night , Eleanor Rigby, Blackbird, Let It Be, All you need is Love and John Lennon’s Imagine. The only song that was really outside the box was Cole Porter’s Night and Day and that was still a good fit for the evening. Melody’s vocals were in top form and the soloists were a joy to hear. Doug Stephenson’s nylon string and steel guitar work was a revelation as, in previous Kimberley concerts, he had been masquerading as a bass player. Because he looks like he is having way too much fun to be legal I do worry about Doug. Clinton Swanson has performed in Kimberley a number of times and his full bodied tenor sax solos, as always, were spot on. Melody’s introductions to the songs were delightful and entertaining.

the rhythmic, melodic and harmonic adventures of Melody Diachun on vocals and shakers, Clinton Swanson on tenor sax and flute and Doug Stephenson on nylon and steel string guitars. Most of the Bossa Nova material was from the pen of Antonio Carlos Jobim and included Quiet Nights (Corcovada), If You Never Come to Me, The Girl from Ipanema, Samba do Aviao, One Note Samba, Dindi, and a nice mish/mash of Insensitive with the Beatles tune Yesterdays. Most of the songs were sung in English with the occasional foray into Portuguese. Although not exactly a Bossa Nova song, but never-the-less appropriate for the evening, the group performed Horace Silver’s jazz classic Song for my Father. Horace’s father came from the Cape Verde Islands that, coincidently, has a rich Portuguese based musical heritage similar to Brazil. Interspersed among Jobim’s songs there were the following Beatles songs Hard Days Night , Eleanor Rigby, Blackbird, Let It Be, All you need is Love and John Lennon’s Imagine. The only song that was really outside the box was Cole Porter’s Night and Day and that was still a good fit for the evening. Melody’s vocals were in top form and the soloists were a joy to hear. Doug Stephenson’s nylon string and steel guitar work was a revelation as, in previous Kimberley concerts, he had been masquerading as a bass player. Because he looks like he is having way too much fun to be legal I do worry about Doug. Clinton Swanson has performed in Kimberley a number of times and his full bodied tenor sax solos, as always, were spot on. Melody’s introductions to the songs were delightful and entertaining.

Bobby Hutchinson and Gary Burton careers’ both somewhat overlapped Jackson’s and they both rose to fame in the 60’s and 70’s. They were the new generation who favored the use of four mallets (two in each hand) that allowed for a more complex pianistic style of performance. Although somewhat now retired Gary Burton is still around and is probably still performing in a semi-professional capacity. Bobby Hutchinson passed away on August 15, 2016 surrounded by his family in the living room of his long time home in Montara, California. He was 75 years old.

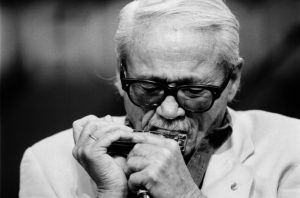

Bobby Hutchinson and Gary Burton careers’ both somewhat overlapped Jackson’s and they both rose to fame in the 60’s and 70’s. They were the new generation who favored the use of four mallets (two in each hand) that allowed for a more complex pianistic style of performance. Although somewhat now retired Gary Burton is still around and is probably still performing in a semi-professional capacity. Bobby Hutchinson passed away on August 15, 2016 surrounded by his family in the living room of his long time home in Montara, California. He was 75 years old. known as “Toots”. The Chromatic Harmonica does not have the same historical traditions of other jazz instruments so he is literally the first of his kind. Although he has played with all the great jazz soloists, including Charlie Parker, he is best known for his composition Bluesette. He died in Brussels on August 22, 2016. He was 94 years old.

known as “Toots”. The Chromatic Harmonica does not have the same historical traditions of other jazz instruments so he is literally the first of his kind. Although he has played with all the great jazz soloists, including Charlie Parker, he is best known for his composition Bluesette. He died in Brussels on August 22, 2016. He was 94 years old.

Her musical co-conspirators are no less impressive. As any good vocalist will tell you a good

Her musical co-conspirators are no less impressive. As any good vocalist will tell you a good  accompanist is hard to find so when you find one you hang onto him and there is no better way than to marry him. Paul Landsberg is that accompanist. The two other members of the trio should be named “The Dynamic Duo”. The drummer Tony Ferraro is a full spectrum performer who can drive a big band into the stratosphere (The Chicago Tribute Band), or dig into funky Latin Grooves with the Gabriel Palatchi Trio or, as in this performance, play whisper soft brushes behind a vocalist. Tony has performed many time in this area. Doug Stephenson is adept on funky electric bass in the context of the Gabriel Palatchi Trio or adding his beautiful bass lines to any acoustic performance.

accompanist is hard to find so when you find one you hang onto him and there is no better way than to marry him. Paul Landsberg is that accompanist. The two other members of the trio should be named “The Dynamic Duo”. The drummer Tony Ferraro is a full spectrum performer who can drive a big band into the stratosphere (The Chicago Tribute Band), or dig into funky Latin Grooves with the Gabriel Palatchi Trio or, as in this performance, play whisper soft brushes behind a vocalist. Tony has performed many time in this area. Doug Stephenson is adept on funky electric bass in the context of the Gabriel Palatchi Trio or adding his beautiful bass lines to any acoustic performance.

to play too loud and dare I say it, often sound unmusical. Andrea promised a tasty treat with Robin Tufts accompaniments and we were not disappointed in his adroit handling of brushes and his simpatico accents. The bassist Stefano Valdo is no stranger to Studio 64 audiences. The last time he was here he played a huge electric bass guitar but this time around he had switched to upright bass. One of his musical heroes is the late great Scott LaFaro of Bill Evans Trio fame. The influences, at least to my ears, were very evident

to play too loud and dare I say it, often sound unmusical. Andrea promised a tasty treat with Robin Tufts accompaniments and we were not disappointed in his adroit handling of brushes and his simpatico accents. The bassist Stefano Valdo is no stranger to Studio 64 audiences. The last time he was here he played a huge electric bass guitar but this time around he had switched to upright bass. One of his musical heroes is the late great Scott LaFaro of Bill Evans Trio fame. The influences, at least to my ears, were very evident  in his free wheeling accompanying and solo style. One of the sonic pleasures of recent years is the return of the upright acoustic bass. Nothing quiet matches the big fat bottom depths of the acoustic upright bass. The first “standard” tune of the evening done in a very original style was Harlem Nocturne. The rest of the program was filled with a number of Andrea’s originals that included You Took Love With You, a nod to Thelonious Monk in Monkey Around (I am sure Thelonious was smiling), and a cute interpretation of a Hungarian Folk tune with some nice hand percussion from Robin. The name of the tune was loosely translated as an ode to a Brown eyed or gypsy girl. It was a neat 4/4 tune with a triplet feel, kind of 6/8, but not really. After the intermission they kicked off with a Latin feel in Andrea’s original Marianna, followed by an achingly slow (Andrea’s direction to the trio) version of the standard The Very Thought of You. This was followed by I Found a New Baby. Then more original tunes including a new untitled work simply called Untitled and the final piece of the evening PMS. A title that doesn’t mean what you think. It is a nod to three modern Jazz master musicians, the bassist John Patitucci the guitarists Pat Metheny and John Scofield – PMS.

in his free wheeling accompanying and solo style. One of the sonic pleasures of recent years is the return of the upright acoustic bass. Nothing quiet matches the big fat bottom depths of the acoustic upright bass. The first “standard” tune of the evening done in a very original style was Harlem Nocturne. The rest of the program was filled with a number of Andrea’s originals that included You Took Love With You, a nod to Thelonious Monk in Monkey Around (I am sure Thelonious was smiling), and a cute interpretation of a Hungarian Folk tune with some nice hand percussion from Robin. The name of the tune was loosely translated as an ode to a Brown eyed or gypsy girl. It was a neat 4/4 tune with a triplet feel, kind of 6/8, but not really. After the intermission they kicked off with a Latin feel in Andrea’s original Marianna, followed by an achingly slow (Andrea’s direction to the trio) version of the standard The Very Thought of You. This was followed by I Found a New Baby. Then more original tunes including a new untitled work simply called Untitled and the final piece of the evening PMS. A title that doesn’t mean what you think. It is a nod to three modern Jazz master musicians, the bassist John Patitucci the guitarists Pat Metheny and John Scofield – PMS.